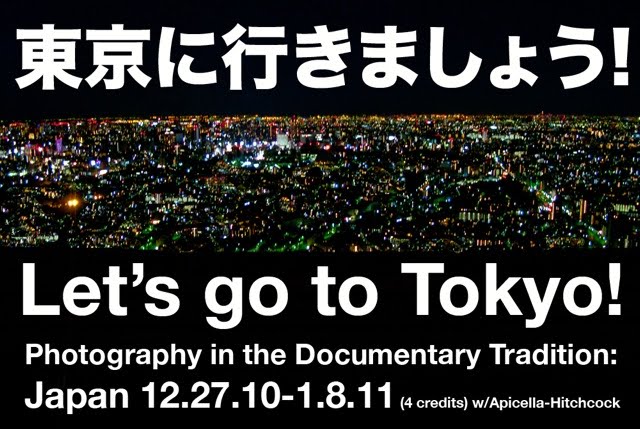

Between April 2009 and March 2010, seven photographers organized a monthly photography exhibition series called “35minutesmen” in a small, long inoperative photo-processing lab in Araiyakushi, a fairly ordinary and slightly inconveniently located neighborhood in Tokyo. Formed around a mall-like street with convenience stores and izakayas [bars offering food] leading from the train station, Araiyakushi is much like many other neighborhoods in Tokyo – a quiet and unlikely home for an alternative exhibition space.

Above the awning of the exhibition space still hangs a sign reading “35mins,” after which the exhibition series took its name. Despite the masculine title, which pays homage in equal parts to the previous life of the space and to San Pedro, California’s finest D.I.Y. band the Minutemen, the series comprised the works of three women and four men who called themselves “Araiyakushi Photographers’ Society,” or “A.P.S.” – an acronym appropriated from the now obsolete alternative film system.

The images that A.P.S. produced were extremely varied. Sake Kota, whose schizophrenic work looks as if it were made by several different conceptual artists, provided the exhibition space. Masayuki Shioda brought the other artists – Junpey Fukumura, Emiko Nagahiro, Tomoko Daido, PAI, and Keisuke Sanada – into the Society. Shioda, who showed two 11×14 images of flora and smaller “scene” shots from the 35minutesmen openings in every show, has also photographed for such magazines as Esquire Japan and Studio Voice (both now defunct), and made a name for himself with his enigmatic “photo brut” images frequently associated with fringe music culture.

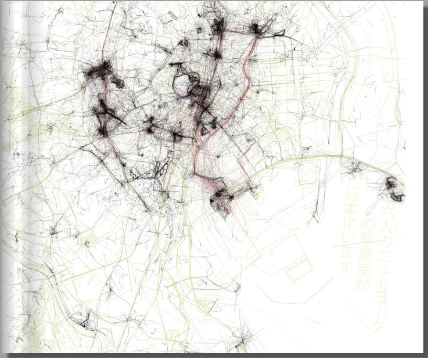

For Shioda, who is also the show’s most articulate spokesperson, “35minutesmen” was akin to a Fluxus event. Most known for its work of the 1960s, Fluxus was an international group of artists whose works aimed to blur the boundaries between art and everyday life, privileging ephemeral works such as multiples and “events,” i.e. performances based on instructional texts, over traditional fine art pieces such as painting and sculpture. Likewise, “35minutesmen” was not simply about the prints displayed on the walls. As Shioda understood it, the entire exhibition process, including the interpersonal relations and circumstances it generated, was the work. In this respect, it may be more accurate to say that “35minutesmen” was like “relational art,” a term Nicolas Bourriand coined to describe work from the 1990s, which instead of offering private experiences, provided situations and encouraged viewers to socially interact with one another and, ideally, even form a community. “35minutesmen” certainly privileged human interactions; it even helped forge new social relations. Before every opening, the local police station had to be informed of the event and subsequently bribed to keep the show from being closed down. On one night, a newly opened Okinawan noodle shop next door (which has since closed) extemporaneously fed gallery visitors. From the last Saturday to Monday of each month, 35minutesmen was a bender, forum for discussing photography, culinary experience, a place for New Zealanders to get together, and others to make new friends, or skateboarding plans.

While relational art emphasizes the production of small and temporary, but nonetheless utopian, communities, “35minutesmen” was much less grandiose; it embraced the contradictions and antagonisms that are necessarily a part of any democratic endeavor. As one might guess from looking at the disparity between the photographs included here, both aesthetic and personal connections between the photographers were, in many cases, tenuous. Oddly for an independently organized and alternative exhibition series, the main thread that tied the photographers together was that all of them except Daido and PAI worked at different times at the same rental photography studio. Of the seven photographers, Fukumura, who now shoots stills on adult video sets, has remained closest to this context of commercial studio photography. In contrast, Daido, a New York resident, shoots expressive, high contrast black-and-white images rooted in the tradition of 1970s street photography. PAI, on the other hand, is a prolific zine publisher, who primarily shoots confrontationally-posed portraits of subjects associated with “street culture.”

Not organized by theme, “35minutesmen” was hardly a group show in the normal sense of the word. The fact that a group of people who have little in common would place arbitrary constraints on themselves to put up a monthly show is what made “35minutesmen” intriguing and remarkable. One story regarding the genesis of the project is that Shioda wanted to motivate his acquaintances, who were not actively showing their work. Another story is that the photographers, who are all roughly in their mid-30s, felt it was one of the last chances before middle age – which they feared would mean “settling down” – to participate in such a project (in fact, one of the photographers is having a baby soon). While the show was very open in terms of the people it drew and variety of works displayed, it was also very controlled, even school-like. As if for a critique, each of the seven photographers had to produce, without fail, a group of prints at the end of each month. On some months they had to put up photos they were unsatisfied with. Some of the photographers had recurring nightmares about the end of the month deadline catching them unprepared. As a frequent visitor to the show, even I felt the guilt of an unproductive month having passed when I was invited to a 35minutesmen opening.

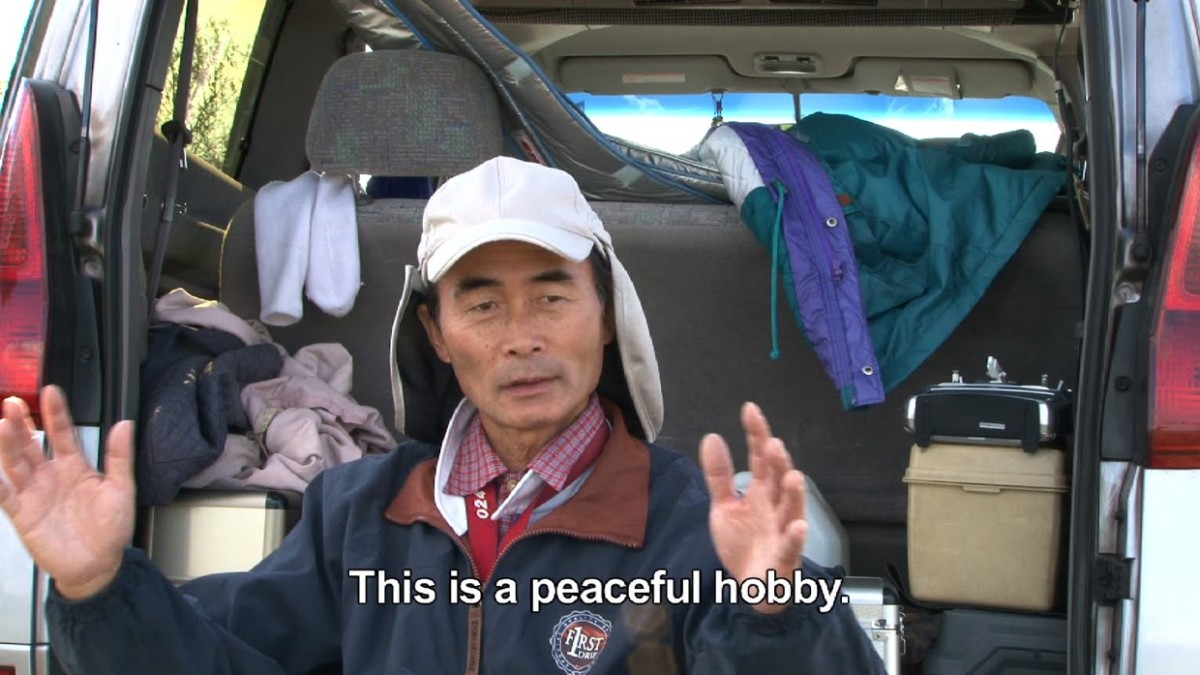

Keisuke Sanada, who once had to return early from a trip to New York to attend “35minutesmen,” cooked on most of the opening nights. He confessed to me recently that cooking was, for him, the most important aspect of the show. In his view, there was no reason to pretend that art openings are about anything other than the drinking, eating, and socializing, particularly in Tokyo where few artworks sell even in more commercial galleries. In this light, it makes sense that 35minutesmen would promote social gatherings rather than private aesthetic experiences, if only for pragmatic reasons. For Emiko Nagahiro, who showed a group of quietly emotive and warmly lit images, the most rewarding aspect of “35minutesmen” was cleaning up the gallery space after the openings. Significantly, Nagahiro and Sanada’s views focus on the catalysts and aftermath of fleeting interpersonal relations produced by the event.

For a show held in an out-of-the-way neighborhood, its biggest achievement may have been its assembling of a truly diverse group of people, among whom were artists, English teachers, photographers, graffiti writers, graphic designers, musicians, art critics, painters, a local bar owner, a street cleaner, a chef, a doctoral candidate, a popular magazine columnist, and an acclaimed fashion designer. To claim that photography is a democratic medium may be commonplace in 2010. “35minutesmen’s” use of photography as a catalyst for fostering democratic social relations, however, was a breath of fresh air, particularly in Tokyo’s contemporary art environment, where do-it-yourself projects too often feel regrettably self-involved.

2009年4月から2010年3月にかけて、7人の写真家達が、いささか交通の便が悪い東京の一角に位置する新井薬師という町の、長らく使われていなかったDPE店において、「35minutesmen」と呼ばれる写真展を毎月開いていた。コンビニや居酒屋が軒を連ねる駅前の商店街を中心に住宅地が広がる新井薬師は、東京の他の町とよく似た静かな地域であって、「オルタナティヴ展示スペース」というイメージからは大分かけ離れた空間だった。

この元店舗の看板には今も「35分」の文字が残されていて、写真展の名前の由来となっている。女性の写真家をも含むにも関わらず、この展覧会は、カリフォルニア州サンペドロが生んだ最高のDIYバンド・ミニットメンにオマージュを捧げる為「minutesmen」と題されていた。実際には、このシリーズ展では3人の女性と4人の男性による作品が展示され、彼らは自らを「新井薬師フォトグラファーズ・ソサエティ」もしくは「A.P.S.」と名乗っていた。ちなみに「A.P.S.」は、今や時代遅れとなった代替写真システム「Advanced Photo System」の略語を拝借したものだ。

A.P.S.メンバー達による写真は多様性を極めていた。まず、複数のコンセプチュアル・アーティストが制作したかに思えるほどスキゾフレニックな作風の酒航太が、この展示スペースの提供者である。そして毎回大四つ切りの植物写真2枚と、「35minutesmen」展のオープニングで撮影した小さな“シーン”写真数枚を展示した塩田正幸が、福村順平、長広恵美子、大同朋子、ペイ、真田敬介といった他の参加者達をソサエティに引き入れた。塩田は、『Esquire Japan』や『Studio Voice』(両誌とも今は廃刊)などの雑誌でも活躍し、マイナーなミュージック・カルチャーに縁が深く、「フォト・ブリュ的」とでも言えそうな作品で名を馳せた写真家である。

このシリーズ展の最も雄弁なスポークスマンでもある塩田にとって、「35minutesmen」はフルクサスのイベントに近いものだ。1960年代の活動が最もよく知られているフルクサスは、多国籍のアーティスト集団で、その作品はアートと日常の境界線を曖昧にすることを目的とし、絵画や彫刻といった伝統的なメディアではなく、マルティプルや“イベント”、つまりインストラクションに基づいたパフォーマンスなどの、 短命な作品を重視していた。「35minutesmen」もまた、単に写真を壁に展示しただけのものではなく、塩田が考えていたように、そこで生まれる人間関係や状況も含め、その全過程を作品の一部として提示したものだった。この意味において「35minutesmen」は、「relational aesthetics(関係性の美学)」に近いものと言えるかもしれない。「関係性の美学」とはニコラス・ブリオーが1990年代の芸術を説明する際に使った言葉で、それは、私的な鑑賞体験を提供する代わりに様々な状況を与えて、そこに参加した者同士が互いに影響を与え合い、理想的にはそれがコミュニティにまで発展する、というものである。「35minutesmen」は明らかに人と人との交流を重視していたし、実際新たな社会的関係を築くきっかけともなった。例えば、毎回オープニング前には近くの交番にイベント開催を知らせなければならなかった彼らは、のちに、イベントを中断させられないように賄賂を贈るようになったのだった。ある晩には、隣に新しく出来た(今は閉店してしまった)沖縄そば屋が、その場の勢いでギャラリー訪問者達にふるまってくれたこともあった。毎月の最終土曜日から月曜日にかけて、「35minutesmen」は酒場であり写真談義のフォーラムであり台所であり、なぜかニュージーランド人の社交場にもなっていたのだった。

「関係性の美学」が、小さく一時的でもユートピア的な共同体を作ることを重視しているのに対し、「35minutesmen」はもっと捌けたもので、民主的な試みにはつきものの矛盾や対立も受け入れていた。ここに含まれた作品相互の不均衡を見れば察しがつくかもしれないが、多くの場合において、彼らの間には美的もしくは個人的な関係性といったものが希薄だった。インディペンデントに組織されたオルタナティヴな展覧会としてはそれも妙な話なのだが、これらの写真家達を繋げていた横糸は、大同朋子とペイ以外の全員が、時期は違えど同じ撮影スタジオで働いていたということだけだった。7人の写真家のうち、AVの撮影現場でスチル撮影等をしている福村が、その商業写真の文脈に現在も一番近いところにいると言えるだろうか。それと対照的なのがニューヨーク在住の大同で、彼女は1970年代ストリート・フォトグラフィーの伝統を受け継ぐ、表現主義的かつハイコントラストな白黒写真を撮っている。一方ペイは精力的な“ジン”の発行者であり、主に“ストリート・カルチャー”界隈の人々を被写体としたポートレイトを撮っている。始めにテーマありきで集まったわけではない「35minutesmen」は、厳密にはグループ展と呼べるものではなかった。ほとんど共通点のない人間同士が集まり、任意の制約を自らに課して、月イチで写真展を開くという事実こそが、「35minutesmen」の魅力であり注目すべき点だったのだ。

このプロジェクトの発端に関してひとつ言うと、塩田は、それまで積極的に作品を見せていなかった知り合いにモチベーションを与えたかったのだという。さらにもうひとつ付け加えると、ほぼ全員が30代半ばであるこの写真家達は、中年——つまりこれは彼らにとって“落ち着く”ことを意味するのだが——に差し掛かり、こういったプロジェクトに参加するのもこれが最後のチャンスだと感じていたらしい(実際作家のひとりにはじきに子どもが生まれる)。この写真展は、招かれた人々の雑多さという意味でも展示された作品の幅広さという意味でもきわめて解放的だったけれども、一方ではかなり束縛的で、ある意味学校のようでもあった。クラスでの批評会のように、7人の作家達それぞれが月末ごとに必ず何点かの写真を制作してこなければならなかったのだ。月によっては、自分では納得出来ていない写真を展示しなければならないこともあったはずだ。そして、気づいたら月末の締切りが迫っていたという悪夢に何度もうなされた者もひとりではなかった。ただの鑑賞者である僕でさえ、「35minutesmen」のオープニングの招待が来る頃になると、今月は無駄に過ごしてしまったという罪悪感に襲われることがあった。

一度「35minutesmen」に参加するためニューヨーク滞在を早めに切り上げて帰国したこともあった真田敬介は、ほぼ毎回オープニングで料理を作っていた。最近彼が僕に打ち明けてくれたところによると、彼にとっては料理をすることこそがこの写真展で最も重要だったのだという。彼にとって、展覧会のオープニングはただの社交場以外であり、それ以上であるふりをする必要は全くないのだった。アート作品がほとんど売れない東京では、なおさらである。そういった実質的な理由からしても、「35minutesmen」が個人の美的経験ではなく社交という側面を押し出したのには納得がいく。 柔らかな光の、静謐かつ叙情的な写真を見せていた長広恵美子が「35minutesmen」で最もやりがいを感じたのは、オープニング後の掃除だったという。ここで特筆すべきは、長広と真田が、このイベントにおいて生まれた儚い人間関係の、きっかけと余波を重要視していたという点だろう。

ひっそりとした町で開かれたこの写真展にあって、その最大の達成は、本当に多彩な人々を呼び寄せたことにあると言えるかもしれない。そこにはアーティスト、英語教師、写真家、グラフィティ・アーティスト、グラフィック・デザイナー、ミュージシャン、美術評論家、画家、近所のバー経営者、清掃員、料理人、博士号志願者、人気雑誌のコラムニスト、一流ファッション・デザイナーなどが集まっていた。2010年にもなって、写真は民主的なメディアであると殊更に主張するのは、当たり前すぎるかもしれない。しかし「35minutesmen」が民主的な人間関係を育むための触媒として写真を利用したそのやり方は、新鮮なものだった。特に、残念ながら多くのDIYプロジェクトが自己陶酔に終わりがちな東京の現状においてそれは、新風を吹き込むものだったと言えるだろう。

Daniel Seiple

Daniel Seiple