Doug Clouse Gravestone Lettering

The Department of Visual Arts at Fordham University is pleased to present the second installment of the Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series with Doug Clouse’s Gravestone Lettering. Over the weeks to come, members from the Department of Visual Arts adjunct faculty will be sharing samplings of their production with the Fordham community.

Currently, the Fordham University Galleries are closed in response to COVID-19. However, our gallery website will continue to feature a robust selection of offerings from the different areas of study offered in the Department of Visual Arts: Architecture, Film/Video, Graphic Design, Painting, and Photography. Stay tuned for increased online presentations, discussions, and public dialogues coming this fall as our gallery website functions as a launching platform for a thoughtful engagement with the issues of our times.

Doug Clouse

Gravestone Lettering

The reason I usually give for my interest in gravestones is my love of lettering and type. I’m a graphic designer, so it is hardly surprising that I am fascinated by the “type” (it is almost always lettering) on gravestones. In addition to their lettering, there is much more to justify research in gravestones: their endless variety of sculptural shapes, their texts, and the connections they maintain to individuals long dead. Each memorial is a micro-history of a person, place, and time.

Cemeteries are packed with life and full of meaning, from the contours of the landscape to the style of lettering on the stones. To read cemeteries and gravestones requires sensitivity and humility. One can learn much about living communities by exploring their cemeteries first, such as whether a town is rich or poor (and when; a community’s economic history is displayed in the scale of its memorials), its cultural ambitions, the skill level of its craftsmen, its ethnic origins, and the calamities it endured. Also, a community’s emotional tone can be gauged by the expressiveness of its memorials; their pathos or restraint indicates whether individuals felt at liberty to express themselves or not.

We tend to think of cemeteries as sad places, and interest in them as somewhat morbid. In a cemetery with expressive memorials, the pathos can tug at you, inviting contemplation of one’s insignificance, the fragile nature of physical satisfaction, and our short-lived connections to others. While respecting the expressions of grief (with the humility mentioned earlier), I resist their gravity by maintaining a sturdy conviction or delusion that I will not be joining the silent throng any time soon. Even inscriptions that speak directly to the living and remind us of our inevitable end, like this well-known one:

Remember me as you pass by,

As you are now, so once was I,

As I am now, so you must be,

Prepare for death and follow me.

don’t oppress me, as I am distracted by speculation about why a gravestone client would choose to remind us of death. Were they angry their time was up? Or perhaps reluctant to forgo one last attempt to exert influence in the world?

Lettering and typography have given focus to my research and interest in gravestones. That research has taken place primarily in two locations: Kansas and New York City.

Kansas

In 2013 and 2014 I made two trips to Kansas to research and photograph gravestones around Wichita, Kansas. My father’s family is from this area and I had noticed well-lettered gravestones on a family visit years before. The lettering looked similar to the nineteenth-century printing style that was the subject of my 2009 book The Handy Book of Artistic Printing, and I wanted to explore the connection between printed typography and inscriptional lettering.

I was very lucky that some Kansas gravestone makers signed their work because I soon discovered the Wichita firm of Kimmerle & Adams, the designers of many of the stones that appealed to me. This firm stimulated my research by focussing my exploration of many small cemeteries in southeastern Kansas and also broadening it to include the social history of Wichita and Kansas. I wanted to know more about Kimmerle & Adams and how they brought a sophisticated style of lettering to a young, raw place like Kansas in the 1800s. Besides cemeteries, I visited local museums and historical societies to learn more about the area.

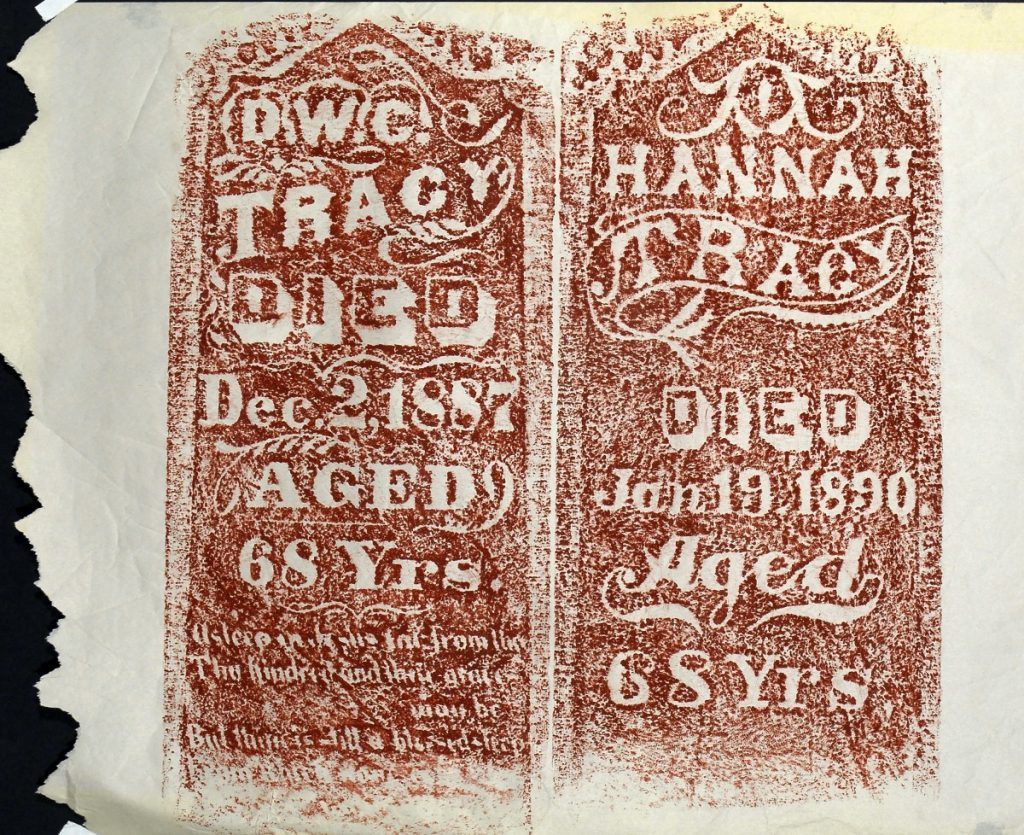

When I encounter fascinating historical design, I’m compelled to make something of or with it. In response to the Kansas gravestones, I took many photos of them and made rubbings of the most visually appealing. The rubbings are basically relief prints that are part historical record, part aesthetic object. They were made quickly with colored wax on gravestone rubbing paper, though when that ran out I used sheets of thin newsprint torn from a roll.

Back home in New York, I compiled my research into an illustrated talk about Kimmerle & Adams that I gave at Cooper Union and also at Hamilton Wood Type & Printing Museum in Wisconsin in 2015. I had high-res photos made of the large rubbings, designed a print of scans of rubbings of the word DIED in many different styles, and made postcards and stickers to give away at my talks.

New York City I live in New York City, where there are millions of graves, marked with memorials as varied as the population. Cemeteries are larger, richer, and more closely administered than in Kansas, so I only recently discovered places to make rubbings of gravestones. Mostly I have explored and photographed the lettering styles at two famous cemeteries, Woodlawn in the Bronx, and Green-Wood in Brooklyn. Because of its location and funding, Green-Wood is much better known than Woodlawn, but Woodlawn boasts a greater variety of lettering styles and a darker, more disheveled landscape. In 2020, I co-hosted a virtual lettering tour of Green-Wood, using photos that I took with my business partner, Angela Voulangas. As I had in Kansas, at Green-Wood I focussed on connections between inscriptional lettering and printing typography.

At Woodlawn, my most exciting discovery related to design has not been the lettering, but rather the unmarked grave of a famous graphic designer, E. McKnight Kauffer. His flat, grassy plot, an obvious gap in a row of gravestones from the 1950s, carries more pathos than any pat inscription, and inspires reflection on the arc of creative careers. Kauffer’s work is celebrated and collected and his home in London is marked with a historical plaque, but he died in poverty and his actual physical remains are nearly forgotten. For several years I have wanted to design and install a memorial for Kauffer, but have not moved beyond getting permission to do so from his descendants in England.

My latest gravestone project in New York City has been to make rubbings of 18th and early 19th-century stones in abandoned cemeteries in Staten Island. Some of the gravestones are disintegrating, so my business partner and I have decided to make rubbings of what we can. Like the Kansas rubbings, these prints are historical records and also images of beautiful things, made in a beautiful way.

The Staten Island gravestone rubbings have inspired rubbings of other historical objects from Staten Island: antique bottle fragments found on the shore. Staten Island has a long industrial history and some of it still washes ashore onto polluted but fascinating beaches. I have been collecting sherds and making rubbings of ones with text on them. These feathery rubbings of broken glass also begin to tell stories of our ancestors’ lives.

For further information on the exhibition please contact: Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock

The Fordham University Galleries are currently closed in response to COVID-19. In the meantime, please visit our gallery website frequently, as our exhibitions are still underway.

For Doug Clouse/The Graphics Office website: click here

For the Visual Arts Department Blog: click here

For the Visual Arts Department Website: click here