Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Lois Martin

The Fordham University Galleries Online

Fordham University at Lincoln Center map

113 West 60th Street at Columbus Avenue

New York, NY 10023

fordhamuniversitygalleries

The Department of Visual Arts at Fordham University is pleased to present the fourth installment of the Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Lois Martin. Over the months to come, members from the Department of Visual Arts adjunct faculty will be sharing samplings of their production with the Fordham community.

The Fordham University Galleries are now open to the general public. As well, our gallery website will continue to feature a robust selection of offerings from the different areas of study in the Department of Visual Arts: Architecture, Film/Video, Graphic Design, Painting, and Photography. Stay tuned for online presentations, discussions, and public dialogues coming this fall as our gallery website functions as a launching platform for a thoughtful engagement with the issues of our times.

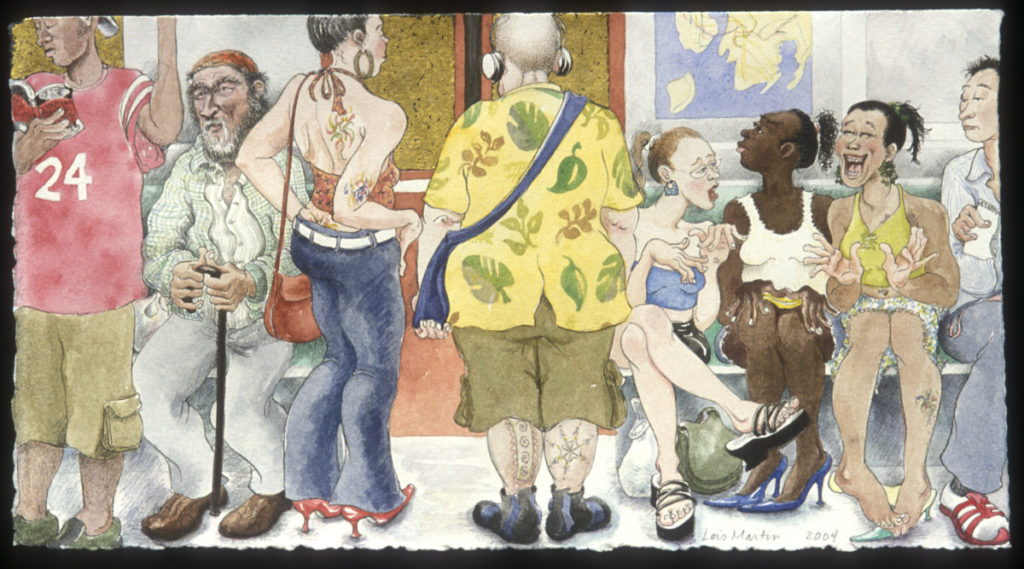

Artist Statement: For many years, I have been creating art about New York City subway riders. The subject compels me; I snatch sketches on the train as I travel, and then put together composites of remembered and imagined scenes in the studio. Children, wry contrasts, and glimpses of drama (whether romance, rage, or camaraderie) are favorite subjects.

I work in a variety of media at a miniature scale. In my mixed media sculptures, I build wire armatures for figure bodies and form heads and hands from polymer clay. The figures are dressed with found scraps, often re-purposed lost gloves or bits of fabric. My watercolor paintings are usually accentuated with gold leaf, and my drawings are executed in silverpoint on prepared paper. I love the way the combination of precious (gold & silver) and commonplace (scraps of paper) seems to reflect the subway setting with its compressed chain of humanity and contrasts of drama and dullness. Smashed up next to a stranger, subway riders don’t know whether their neighbor is a murderer or a Nobel Laureate—or who has just committed a robbery, won a lottery, or been diagnosed with a terminal illness. Sparks of emotion suggest optimistic or pessimistic readings, but there is no overarching narrative.

I work slowly, loading great detail into each compressed image. Often I work in a scroll format, representing a horizontal line of seated and standing figures. Together, the linear format, miniature scale, and richness of detail hopefully pull viewers into this mysterious subterranean orbit.

Image Caption: Lois Martin, Hawaiian Shirt, 2019, watercolor, 6 x 11 inches.

For further information, contact Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock.

For the Visual Arts Department Blog: click here.

For the Visual Arts Department Website: click here.

Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series & Book: Anibal Pella-Woo: “Almost 2.0”

The Department of Visual Arts at Fordham University is pleased to present the first summer installment of the Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Anibal Pella-Woo: Almost 2.0. As well as being the first offering of the season, this project is the inaugural publication for Hayden’s Books. Hayden’s Books will be producing an ongoing series of publications focusing on artist projects, research, critical writings, and works in progress. This publication series honors Hayden Hartnett, a much-loved visual arts major. Please stay tuned over the weeks to come as members from the Department of Visual Arts adjunct faculty and artists at large share samplings of their production with the Fordham community in our Hayden Hartnett Project Space (online) and in this exciting new book series.

The Fordham University Galleries are open to the general public provided that visitors complete a temperature check and brief screening according to university health protocols (the gallery is accessible for those on campus registered with VitalCheck). Additionally, our gallery website will continue to feature a robust selection of offerings from the different areas of study offered in the Department of Visual Arts: Architecture, Film/Video, Graphic Design, Painting, and Photography. Stay tuned for online presentations, discussions, and public dialogues coming this summer as our gallery website functions as a launching platform for a thoughtful engagement with the issues of our times.

Artist Statement:

2.0: “used post-positively to describe a new and improved version or example of something or someone.”

In 1999, I bought my first digital camera. It produced a 1.92-megapixel image file.

Almost 2.0

Book Link

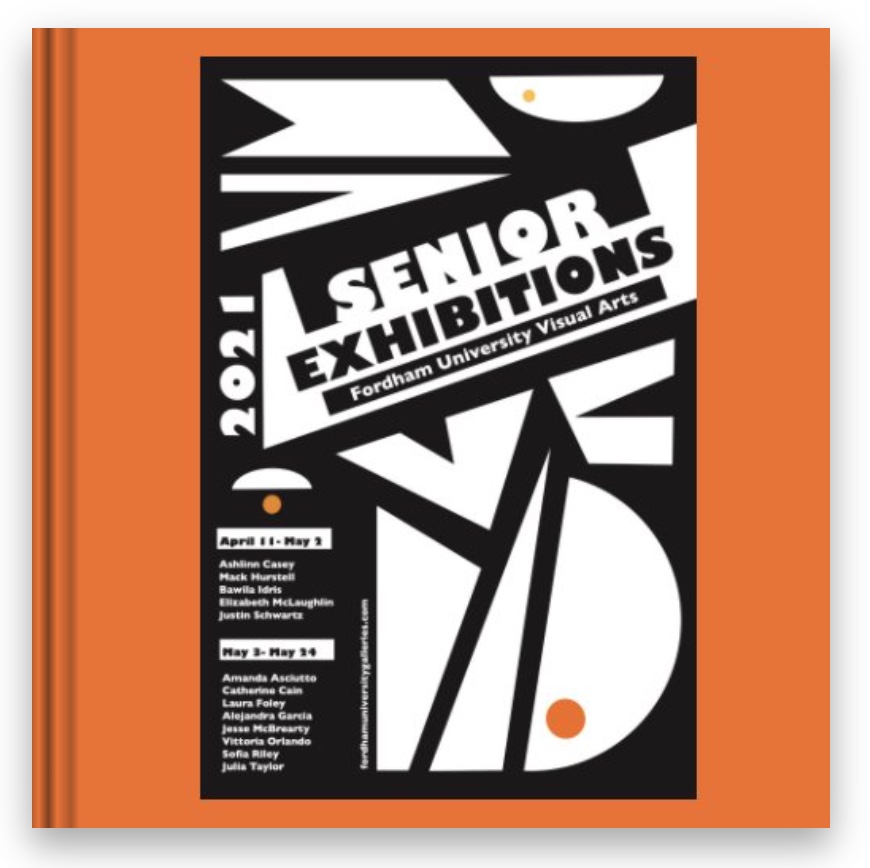

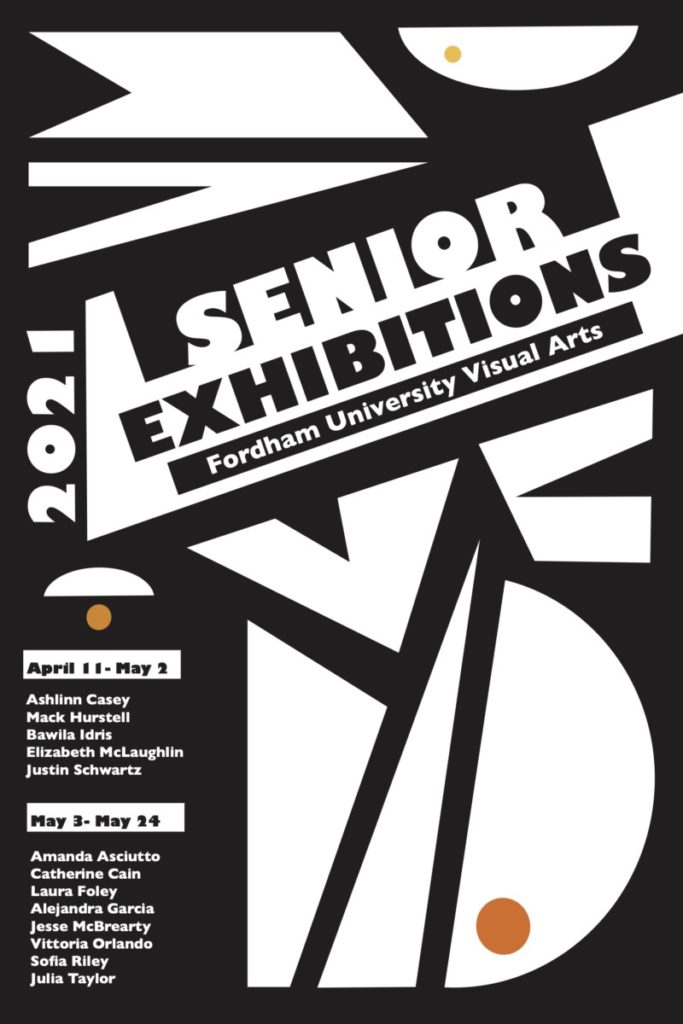

New book: 2021 Senior Thesis Exhibitions

Hot off the press—the 2021 Senior Thesis Exhibitions book by Amanda Asciutto, Catherine Cain, Ashlinn Casey, Laura Foley, Alejandra Garcia, Mack Hurstell, Bawila Idris, Jesse McBrearty, Elizabeth McLaughlin, Vittoria Orlando, Sofia Riley, Justin Schwartz, and Julia Taylor is now available. Edited by Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock with a fantastic cover design by Natalie Norman-Kehe. 142 pages of amazing work by our graduating artists!

2021 Senior Thesis Exhibitions: Small Square, 7×7 in, 18×18 cm, 142 pages is available to preview and purchase here.

New Books—Digital Photography Volumes 2 & 3 Out Now

The speed at which one can learn the principles of traditional analog photography during a typical school semester is relatively quick. Things are humming along smoothly by week number seven, with students having a working understanding of camera operations, film processing, and the development of contact sheets and prints. Around week seven, we begin to switch gears from focusing on the technical to concentrating on meaning and communication strategies. The remaining eight weeks are devoted to exploring what one wants to say about the world, how to go about it, and how to read and discuss photographs.

The speed at which one can learn the principles of digital photography is absurdly accelerated compared to traditional photography. Within the first five classes, we are already up and running and understand camera usage and how to employ the computer for image management, adjustment, and output.

Three months ago, these students were pushed into the deep end of the photographic pool of digital photography and asked to swim almost immediately. They rose to the challenge admirably. Their selections for this book represent their speedy technical proficiency; moreover, their images show their intelligence, distinct personalities, and concentrated engagement with the world.

Enough said, enjoy! —Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock

Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Vincent Stracquadanio

The Department of Visual Arts at Fordham University is pleased to present the third spring installment of the Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Vincent Stracquadanio. Over the weeks to come, members from the Department of Visual Arts adjunct faculty will be sharing samplings of their production with the Fordham community.

The Fordham University Galleries are currently closed to the general public in response to COVID-19 (open for those on campus registered with VitalCheck). However, our gallery website will continue to feature a robust selection of offerings from the different areas of study offered in the Department of Visual Arts: Architecture, Film/Video, Graphic Design, Painting, and Photography. Stay tuned for online presentations, discussions, and public dialogues coming this spring as our gallery website functions as a launching platform for a thoughtful engagement with the issues of our times.

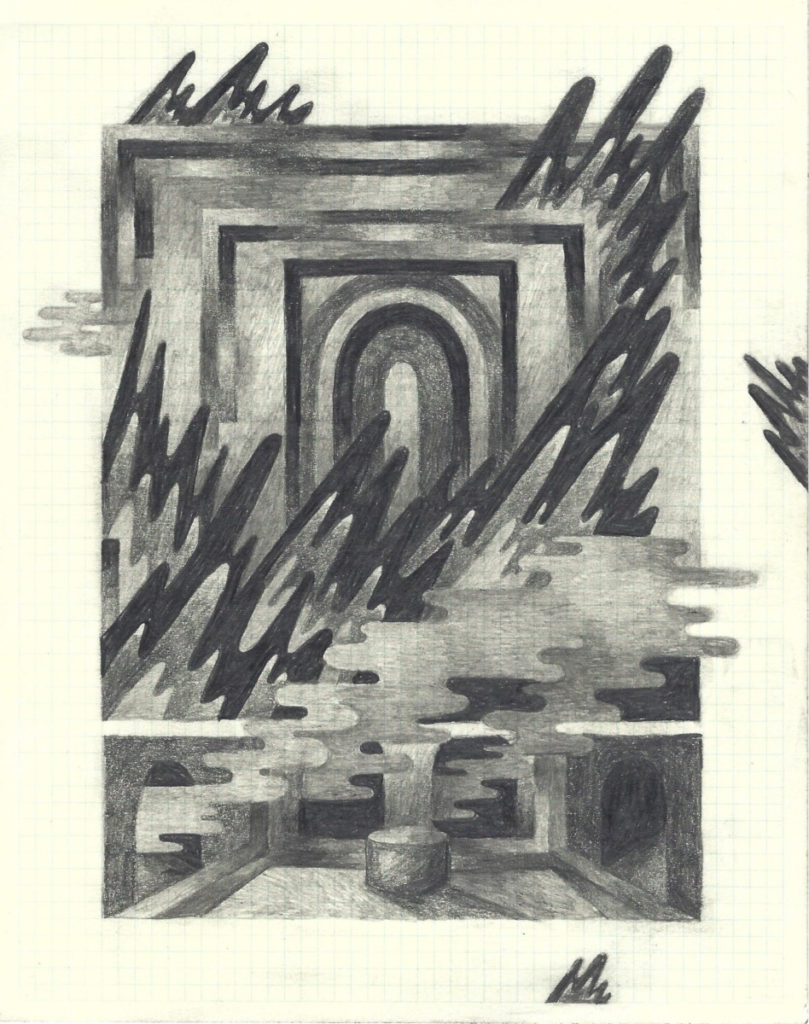

Artist Statement: My work depicts spaces of transformation and magic. These lavish interior spaces collapse and extend using patterning and flatness that eliminates hierarchies between front and back, foreground and background.

The rich patterning of these spaces is dense with visual surprise and full of organic references, geometry, personal history, horror films, and antiquities. Each picture not only exhibits an interior logic but also presents distinct idiosyncrasies suggesting differentiation in time, event, or architecture.

Some spaces are filled with foreboding forms such as dark fire and cloud-like mists that appear to seep through various spaces disrupting spatial certainty. Others, silhouetted figures and latticed patterns line corridors and form structures for rhythm and magic. In many, lingering shadowy hands cradle and loom over these spaces, suggesting a menacing presence that creates and holds these spaces together.

Artist Bio: Vincent Stracquadanio is an artist living and working in New York City. He earned his MFA from the Yale School of Art and a BA in visual arts from Fordham University. He has been exhibited at Good Naked Gallery (NY), New Release (NY), Trestle Gallery (NY), Artspace (CT), among others. He was a nominee for the Rema Hort Mann Emerging Artist Grant and received both the Gamblin Paint Award and James Storey Memorial Visual Arts Award. Stracquadanio has taught at the Yale University Art Gallery and is currently a museum educator at the Jewish Museum and an adjunct professor at Fordham University.

For further information on the exhibition, please contact Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock.

The Fordham University Galleries are currently closed in response to COVID-19. In the meantime, please visit our gallery website frequently, as our exhibitions are still underway.

New course: Phone to Book

Department of Visual Arts Senior Thesis Exhibitions

The Fordham University Department of Visual Arts is pleased to announce the start of the 2021 Senior Thesis Exhibitions. Please follow our talented emerging artists as they exhibit throughout the spring semester. Part one is now available online.

For further information on the exhibition, please contact Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock.

The Fordham University Galleries are currently closed to the public in response to COVID-19. In the meantime, please visit our gallery website frequently, as our exhibitions are still underway.

Walis Johnson: The Red Line Archive

The Department of Visual Arts is pleased to present the Fordham University Galleries Online second installment of 2021, a portfolio of projects by the filmmaker, educator, walker/researcher Walis Johnson. Our gallery regularly features a body of work by a contemporary artist, alternating with our Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series, in which our talented adjunct faculty share samplings of their production with the Fordham community.

The Red Line Archive by Walis Johnson is a mobile public art project that engages New York City residents in a conversation about race and the history of the 1938 Red Line Map that helped create the segregated urban landscapes of the city. This “cabinet of curiosities” is wheeled along city streets, inviting people to freely associate about personal artifacts and documents from the artist’s family history in gentrifying Brooklyn and ephemera collected during four artist walks in and along the periphery of redlined neighborhoods.

Redlining refers to discriminatory lending practices that prevented African-Americans (and other people of color) from attaining home mortgages and business loans in New York City and urban communities nationwide. Even as loans to blacks were discouraged, real estate brokers actively used racial and economic fear-mongering that encouraged white homeowners to sell their properties at reduced prices and move en masse to new suburbs created for them. This was known as white flight.

Neighborhoods of historic and cultural importance in Black Brooklyn such as Bedford-Stuyvesant, Fort Greene, and Crown Heights – areas now on the frontline of gentrification – went from racially diverse to black “ghettos” almost overnight as redlining excelled. These neighborhoods physically declined as city services and economic development were withheld. Redlining was not solely confined to African-American neighborhoods; areas like Greenpoint, Williamsburg, and Dumbo, among others, were redlined, too.

Red Line Labyrinth is a site-specific participatory art installation enacted in neighborhoods at the epicenter of aggressive gentrification and displacement. Labyrinths have been used throughout human history as a means to inspire personal and community reflection and renewal. The artist installed the labyrinth at Weeksville Heritage Center on October 18, 2017. Weeksville is the site of one of the first free Black communities in Brooklyn. Participants walked the Labyrinth alone or in pairs to activate reflection on the practice of redlining and its effects on their life and family in the past and present. Each person enacted the experience of healing and pilgrimage as they walked. Produced and Edited by Walis Johnson, Cinematography by Teodora Altomare.

About the artist:

Walis Johnson is a filmmaker, educator, walker/researcher interested in the intersection of documentary film and performance whose work documents the urban landscape through ethnographic film, oral history, and artist walking practice. She holds a BA in History from Williams College and an MFA from Hunter College, in Interactive Media and Advanced Documentary film. She has taught at Parsons School of Design.

Walis Johnson’s essay Walking the Geography of Racism has been published in a new anthology entitled In Search of African American Space: Redressing Racism, edited by Jeffrey Hogrefe and Scott Ruff with Carrie Eastmond and Ashley Simone. The anthology is published by Lars Müller Publishers. The essay focuses on Johnson’s artist walking practice and The Red Line Archive Project of the past few years. It is a truly beautiful book with essays by an important group of architects and artists who think deeply about architecture, performance art, history, and visual theory, exploring the creative relationship between the African diaspora and social space in America.

The Red Line Archive

The Gotham Center—The Red Line Archive: An Interview With Walis Johnson

For further information on the exhibition please contact Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock.

The Fordham University Galleries are currently closed to the public in response to COVID-19. In the meantime, please visit our gallery website frequently, as our exhibitions are still underway.

New Exhibition: Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Željka Blakšic

Adjunct Faculty Spotlight SeriesŽeljka Blakšic AKA Gita Blak: Connect the DotsThe Fordham University Galleries Online Adjunct Faculty Spotlight SeriesŽeljka Blakšic AKA Gita Blak: Connect the DotsThe Fordham University Galleries OnlineFordham University at Lincoln Center map 113 West 60th Street at Columbus Avenue New York, NY 10023 fordhamuniversitygalleries The Department of Visual Arts at Fordham University is pleased to present the second spring installment of the Adjunct Faculty Spotlight Series: Željka Blakšic AKA Gita Blak: Connect the Dots 2019. Over the weeks to come, members from the Department of Visual Arts adjunct faculty will be sharing samplings of their production with the Fordham community. Currently, the Fordham University Galleries are closed to the general public in response to COVID-19 (open for those on campus registered with VitalCheck). However, our gallery website will continue to feature a robust selection of offerings from the different areas of study offered in the Department of Visual Arts: Architecture, Film/Video, Graphic Design, Painting, and Photography. Stay tuned for online presentations, discussions, and public dialogues coming this spring as our gallery website functions as a launching platform for a thoughtful engagement with the issues of our times. Željka Blakšic AKA Gita Blak, Connect the Dots, 2019, Polymer relief print on Arches Cover, 13 x 18 inches, printed by Ruth Lingen at Line Press Ltd and published by Planthouse GalleryConnect the Dots by Željka Blakšic started years ago as a drawing game made for a Game Night series of free public events presenting artist-made games, organized by Sheetal Prajapati and Anna Harsanyi at Soho20 Gallery in New York City. Participants were invited to connect the dots in order to reveal and discover a female revolutionary portrait. All the women represented in the series of prints played a pivotal role in their community and later society; as activists, theorists, educators, and politicians in launching the revolution or bringing in a monumental social change that enriched the lives of many. Here we remember them and celebrate their bravery, selflessness, dedication, and complexity. Željka Blakšic AKA Gita Blak is an interdisciplinary artist and educator who works with performance, 16mm film, video, and installation. Her practice is often collaborative and inspired by the sub-culture of the 1990s-era in Croatia when punk, anarcho, and eco movements were having a renewal. Resistance manifested itself through the cooperation and gathering of different alternative social groups and this experimental environment became a university of rebellion–a key force, giving voice to new expressions of democracy, justice, common values, and free speech. Blakšic often collaborates with members of different subcultures, activists, schoolgirls, singers, urbanists, and students, creating sites and praxis of collectivity. Using pedagogical methodologies within the context of contemporary art she organizes workshops, creates publications, makes films and exhibitions.Recent exhibitions include “It Won’t Be Long Now, Comrades!” curated by Inga Lace & Katia Krupennikova at Framer Framed in Amsterdam; “The Witnessing Event” curated by Rashmi Viswanathan at Los Sures Museum in NY; “BROUHAHA” project at Recess SoHo; “Claim Space” performance at Museum of Modern Art, NY; Artizen Cluj, Romania; BRIC Contemporary Art Gallery, NY; Gallery Augusta, Helsinki; District Kunst- und Kulturförderung, Berlin; AIR Gallery, NY; Active Space, NY; Urban Festival in Croatia; Gallery of SESI, Sao Paolo, Brazil; The Kitchen, NY and The Khyber Center for the Arts in Canada. She was a recipient of the Residency Unlimited & National Endowment for the Arts Award 2017, New York USA; Cittadellarte – Fondazione Pistoletto Residency 2017, Biella, Italy; Recess Session commission 2016, New York USA; A.I.R. Gallery Fellowship Program for emerging women artists 2014/15, New York USA; The District Kunst Award 2013, Berlin; New York Foundation for the Arts Residency 2012, Paula Rhodes Award 2010, New York USA, and many others. Most recently she was a resident at Alserkal Avenue in Dubai, UAE. Image caption: Nadezhda Krupskaya (1869 – 1939) was a Russian Bolshevik revolutionary, activist, and politician who believed that access to education was a step towards improving people’s lives. She was a historian and a theoretician of educational science in addition to being one of the main organizers of the socialist system of education. She served as the Soviet Union’s Deputy Minister of Education from 1929 until her death in 1939. A committed Marxist, she encouraged the development of a library system in the Soviet Union. She was the wife of Vladimir Lenin from 1898 until his death in 1924. For further information on the exhibition please contact: Stephan Apicella-Hitchcock The Fordham University Galleries are currently closed in response to COVID-19. In the meantime, please visit our gallery website frequently, as our exhibitions are still underway. For Željka Blakšic’s website (AKA Gita Blak) click here. For the Visual Arts Department Website: click here. |